Alasdair Gray’s The Book of Prefaces was published 20 years ago. I first heard of it as work-in-progress in the summer of 1998 when I received “a begging letter”, as he put it, from its beleaguered author. Alasdair said he was literally begging various writers and academics to help him complete the book which he was contracted to produce for Bloomsbury and had been working on for a decade. It was to be “THE BOOK OF BOOKS” in that it brought together prefaces to their own work by great writers throughout history: “Mostly the mighty dead whose copyrights have lapsed.” Alasdair had a great sense of humour and in calling The Book of Prefaces “A BOOK FOR TODAY” he added “Only the rich and illiterate can ignore our anthology. With this in their lavatory everyone else can read nothing but newspaper supplements and still seem educated.” The idea of the book was to give a history of literature, specifically great books, in the introductory words of their authors.

In his letter Alasdair attached a list of works that still required entries. Payment for help was to comprise a portrait by Alasdair. Who could refuse such a request? I had just finished lecturing on two writers on the list, so I wrote back saying I would be glad to take on William Wycherley and William Congreve. I drafted two critical contributions on those two 17thcentury Restoration playwrights. As overall author of the volume, Alasdair reserved the right to edit these pieces as he pleased, and in the event he completely rewrote my entries.

In my lecture I had challenged the view of Restoration comedy as frivolous “Fun with Wigs”, to quote the title of a 1995 David Baddiel documentary on the subject. My lecture used contemporary documents, the writings of John Milton and the work of Michel Foucault to suggest that these Restoration dramatists were not reactionary fops. For me there was continuity between Milton’s divorce pamphlets of the 1640s and the plays of Wycherley and Congreve: both were critical of the institution of marriage.

When it came to the contributor’s portrait I told Alasdair that there was really no need, thinking of how precious his time was, but he absolutely insisted. I was duly booked in for the afternoon of Friday 4th of December 1998. I can be precise because Alasdair dated the portrait. I had imagined a sitting for a portrait to mean staying still for an hour or more, a thing I found almost impossible to do, but Alasdair allowed me to relax and chatted away, asking me questions while he was drawing. We shared stories about Glasgow’s East End back in the day. Alasdair grew up in Riddrie, and my father – who was a lot older – was raised in the Calton. I remember Alasdair seemed a bit wheezy and I asked him if he had an inhaler. He said yes, but he didn’t like to overuse it. I told him I puffed away on mine whenever I felt a wheeze coming on. I couldn’t imagine sticking to the recommended dose if it meant being breathless. Alasdair laughed; he obviously had more sense. We talked about Glasgow, Irish and Scottish literature, and Scottish independence. I suggested to Alasdair that what he was doing was telling a story about literature through prefaces. I said I was interested in Jacques Derrida, a philosopher who was fascinated by the marginal texts that framed major works. Derrida was writing a history of philosophy through prefaces and postscripts and minor texts that shone a light on larger ones. I felt Alasdair was engaged in the literary equivalent. He was curious when I made the comparison, but remained resistant to Derrida’s approach to literature, which he considered to be too theoretical.

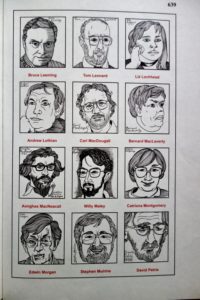

Alasdair made two versions of my portrait, one tinted and one black and white. I never realised at the time that the portraits would appear in the book. When The Book of Prefaces was finally launched in 2000 it included an “Index of Helpers” and a section entitled “Portraits of Contributors” with 21 postage-stamp sized images, most of them done especially for the book, although he had made a couple earlier, such as Archie Hind’s in 1970, and Elspeth King’s in 1977.

Alasdair made two versions of my portrait, one tinted and one black and white. I never realised at the time that the portraits would appear in the book. When The Book of Prefaces was finally launched in 2000 it included an “Index of Helpers” and a section entitled “Portraits of Contributors” with 21 postage-stamp sized images, most of them done especially for the book, although he had made a couple earlier, such as Archie Hind’s in 1970, and Elspeth King’s in 1977.

The dustjacket described this unique volume as “A Short History of Literate Thought in Words by Great Writers of Four Nations from the 7th to the 20th Century Edited & Glossed by Alasdair Gray Mainly”. The publisher’s blurb included a paragraph on Alasdair’s little helpers: “While Alasdair Gray has chosen and edited all the prefaces and  written most of the commentary, he has been assisted by some thirty authors who have also written commentaries. These include James Kelman, Janice Galloway, A. L. Kennedy, Bernard MacLaverty, Liz Lochhead, Roger Scruton and, indeed, Virginia Woolf.”

written most of the commentary, he has been assisted by some thirty authors who have also written commentaries. These include James Kelman, Janice Galloway, A. L. Kennedy, Bernard MacLaverty, Liz Lochhead, Roger Scruton and, indeed, Virginia Woolf.”

I can’t speak for any of the other contributors, not having seen their original submissions, but although I’m credited with “glosses on WYCHERLEY’S THE COUNTRY WIFE and CONGREVE’S THE WAY OF THE WORLD” the entries themselves are entirely Alasdair’s. I found it interesting that he chose to focus more on biographical information and on what seemed to me a quite conventional way of seeing these writers – as conservative rather than subversive.

The original portrait is drawn on the cardboard backing for a pack of Marks & Spencer recycled paper. In characteristic Alasdair fashion he annotated the portrait around the frame with the words “WILLY MALEY FRIDAY 4.12.1998. This is the original drawing, untinted since I suspect that colour would obscure the purity of the line: or (if not purity) clarity…”

I never got dressed up for the portrait, it being just a headshot, but I had on an old sweatshirt that was a rich red colour and Alasdair remarked on it. When it came to making the tinted version Alasdair took the rich red colour out of the sweatshirt and put it into the background.

I never got dressed up for the portrait, it being just a headshot, but I had on an old sweatshirt that was a rich red colour and Alasdair remarked on it. When it came to making the tinted version Alasdair took the rich red colour out of the sweatshirt and put it into the background.

The Book of Prefaces is dedicated “TO PHILIP HOBSBAUM POET, CRITIC AND SERVANT OF SERVANTS OF ART.” In that case, I must be a servant of a servant of servants of Art because, as Alasdair’s helper, I was helping him, as critic, to help the artists whose work was gathered in the book. It is the most eccentric and most interesting project I’ve been involved in and the one where I feel I was paid most handsomely for the least labour.